This article appears in the 2024 Fall Long Trail News and was written jointly by GMC’s Communications Manager Chloe Miller and Education and Volunteer Coordinator Lorne Currier.

When Keegan Tierney, GMC’s Director of Field Programs, interviewed for his job in 2017, he said “You’ll never see me build a waterbar.” A few years later, Keegan admits that the legacy (read: steep) trails of the Long Trail System need thousands of these stone or log drainage channels, and installing, repairing, and clearing them is essential to managing the Long Trail System.

So, what’s a waterbar, how does it work, what happens when one fails, and why are waterbars imperfect but necessary structures on Vermont’s steep and rugged trails?

If you read the previous installment of “Trail Talk,” exploring the purpose and design of common trail features, you know trail builders try to keep people on trails, and water off them. In Vermont, those goals go hand in hand.

A waterbar is a simple channel cutting diagonally across a trail, diverting surface water that would otherwise run down the trail (removing surface soil as it goes), and instead dispersing it into the woods. Like brush-ins, effective waterbars must be well-designed, built, and maintained to do their job of handling water and holding up to hiker traffic.

In a Perfect World

Waterbars work well when built and maintained properly, but they fail easily. If we were to start over and build the nearly 500-mile Long Trail System today, we would follow sustainable grades and use modern trail building techniques to avoid the need for so many waterbars. But our century-old trails often take the steepest route up a mountain. That’s, coincidentally, the same route water wants to flow down.

Years of deferred maintenance means a good chunk of these waterbars are clogged or otherwise failing. And we must continually invest in better drainage for today’s and tomorrow’s extreme rainstorms.

Building and Repairing Waterbars

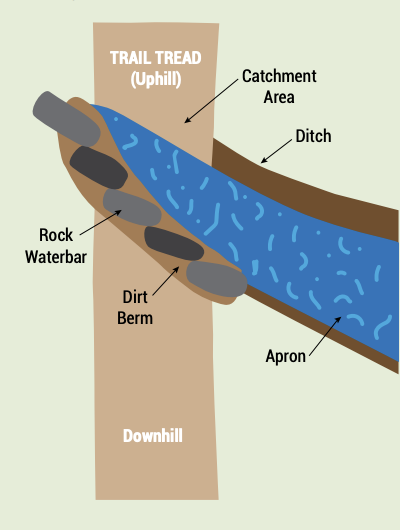

A waterbar has a few components: The rock or log bar itself; the catchment area above it, where water is intercepted; the ditch conveying water off the trail; the apron, or drainage area where water spreads across the forest floor; and the dirt berm above and below the bar.

On the Long Trail, most waterbars are built with rock, which is more durable than wood. An effective waterbar extends well beyond each side of a trail, at least three feet into the surrounding forest, so a) water will not find its way back on to the trail and b) hikers are not tempted to step around the large stones of the bar in the middle of the tread.

The ideal waterbar is set at a 45-to-60-degree angle across the trail, with stones arranged in a shingled manner so the upper ones overlap the lower ones.

Rocks must be set securely into the tread and reinforced with crushed stone and mineral soil to keep them in place. The berm above the bar separates rocks from water, so that the base around the rocks doesn’t erode away.

Waterbars can fail for a few reasons:

- The waterbar is too narrow, insufficiently hardened, and annoying enough that hikers go around it instead of over. This compacts the soil at either end of the waterbar, and allows water to find its way back to the trail. It can be prevented by extending the waterbar beyond the edge of the treadway and hardening its ends to make walking over the waterbar the easiest route.

- A rock in the bar is either too small or improperly set and becomes loose, creating a weak point for water to sneak past and travel down trail. In this case the waterbar will probably need to be rebuilt.

- Organic debris (leaves, sticks, trail sediment) fills the ditch and catchment area to the point that water overtops the bar and continues down trail. This is prevented by regular and thorough maintenance.

Unfortunately, the large storms we now see so often can sometimes overtop the best waterbar.

Critical Routine Maintenance

Every fall, and after heavy rain, waterbars fill with fallen leaves and trail sediment. Then water can overtop the drain and rush down the trail, removing the trail surface as it goes.

Overflowing waterbars have compounding effects, because they increase the volume of water the next downhill waterbar must handle. A big storm can wash out an entire trail from just one or two poor drains at its top.

Caretakers and volunteer trail adopters perform the critical maintenance of cleaning waterbars, using trail tools like hazel hoes, mattocks, or even their boots or hands to move all organic material and accumulated sediment to the downhill side of the trail. They clear the drain down to mineral soil — the dense, durable, light-brown material beneath the easily eroded topsoil.

Maintainers must ensure a smooth gravitational path for water; any upgrade or flat spot will cause water to pool and the waterbar to fail. If there are gaps in the stones of the bar, maintainers block them by a berm of mineral soil. They may alert GMC headquarters if reconstruction is needed.

As rainfall becomes more intense, waterbars become more important, and good training of volunteers is vital.

Noticing Waterbars As a Hiker

Now that you understand waterbars, watch for them on your next hike. If it’s raining, watch them in action – diverting water from the trail – or failing, with water overtopping them and continuing down the trail. You can also help us reduce future maintenance needs by stepping up and over a waterbar, not around.

Leave a Reply