Thanks to Stephanie Graudons and Ted Letcher of Great Range Frames for their expertise and photos in this article. Stephanie has an “undercast obsession,” and Ted, an atmospheric research scientist, has some tips on how to predict the temperature inversions and conditions that cause an undercast.

If you’re a member of GMC’s Facebook group or a frequent social media user, you may have seen several stunning photos over the last few weeks of soft sunrises over mountain peaks with thick layers of clouds obscuring the view below. These heavenly “undercasts” (like overcast, but below) are found when atmospheric conditions are just right here in Vermont.

If you’re a member of GMC’s Facebook group or a frequent social media user, you may have seen several stunning photos over the last few weeks of soft sunrises over mountain peaks with thick layers of clouds obscuring the view below. These heavenly “undercasts” (like overcast, but below) are found when atmospheric conditions are just right here in Vermont.

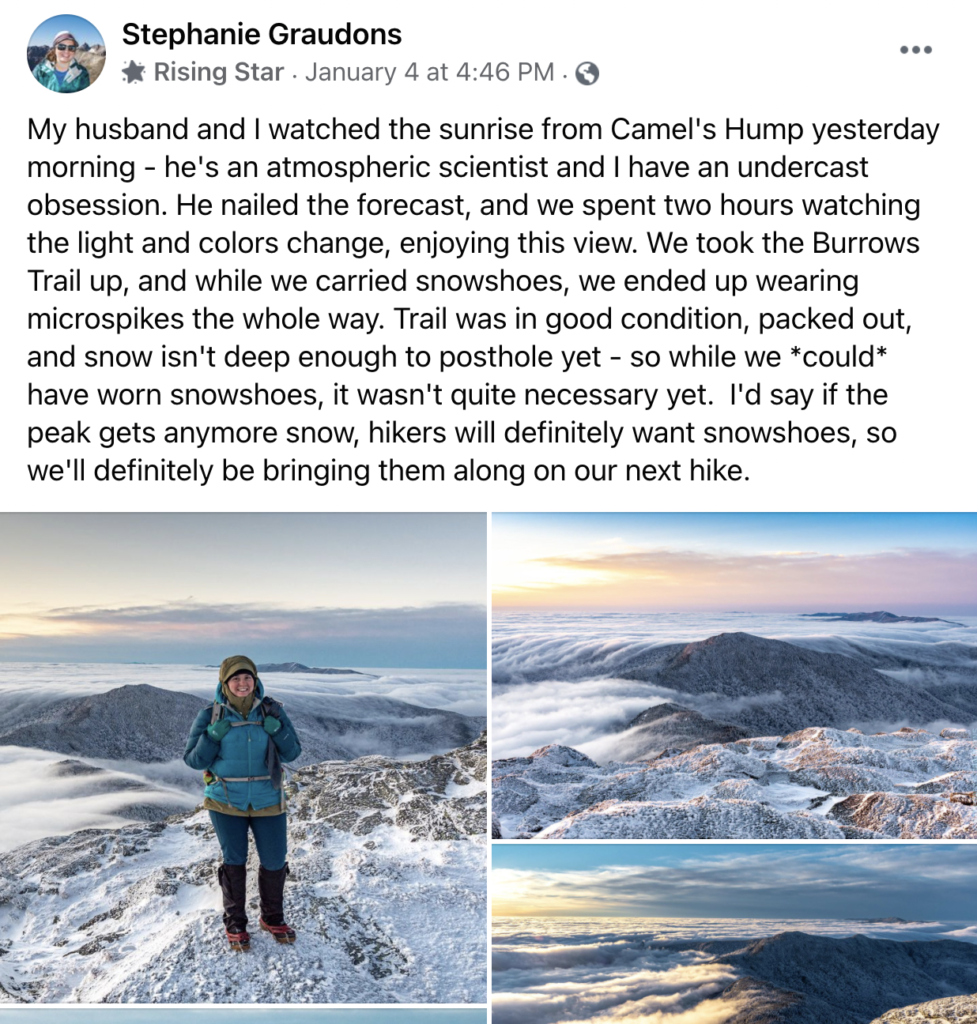

Many hikers seek out the view, the feeling of being perched above the clouds, only to find the summit obscured in fog or winds dissipating the clouds below. GMC caught up with Stephanie Graudons and Ted Letcher, Vermonters, avid hikers, and GMC volunteers who have a self-admitted “undercast obsession” — and understandably so. Stephanie is a photographer whose photos of an early January undercast went certifiably viral on GMC’s social media pages, and Ted has a PhD in Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology, with research focused on mountain-specific meteorology. They gave us some tips and tricks to maximize your chances of catching the breathtaking phenomenon. The biggest takeaway? Like many things with hiking, there’s no guarantee.

It’s always sunny if you climb high enough, right? — Stephanie Graudons, on her blog

Temperature and other weather conditions

The most basic ingredient of an undercast is a temperature inversion, where the temperature increases with height rather than decreases. The inversion layer acts as a “lid” that can lock the clouds in at lower atmosphere. In Vermont, inversion layers around 2500′-3500′ feet high are best suited to creating a cloud layer that’s actually visible from a Green Mountain summit, instead of enshrouding it.

Calm wind can also prevent the cloud layer from dissipating too quickly, or prevent clouds from being pushed up over the summit.

Conditions may be just right for an undercast in between storm systems, when moisture left behind from a departing storm is trapped in the lower atmosphere, and weak high pressure builds in advance of the next storm. In Vermont, this is often ideal when storm systems travel in from the southwest. Another favorable setup is one where weak high pressure persists over the Maine coast, helping to bring in moisture from the Atlantic. However, in this setup, the low clouds tend to get held up on the Presidential Range in New Hampshire, and do not make it to Vermont.

Interested in tracking incoming inversions and cloud layers yourself? “You certainly don’t need a degree in meteorology, but you do need to have some understanding of how to read various diagrams and know what they mean,” says Stephanie. They suggest tracking large-scale weather patterns on global models; cloud cover and winds from regional models; and vertical profiles of temperature, humidity, and wind.

Timing it Just Right

Ted cautiously says, “I’m coming around to this idea that the best season is late fall to early winter, when the sun is at its lowest elevation in the sky.” The higher and brighter the sun, the stronger the solar energy that heats the ground and will break up or move the cloud layer, ruining the undercast. During the fall and winter, undercasts can persist throughout the day, but sunrise is typically best for the most uniform cloud deck, before solar energy is at play.

Where to Go and How to Get There

Mountains in Vermont that are more isolated or prominent, such as Camel’s Hump or Mount Mansfield, are generally more conducive to a 360-degree undercast. This is because air carrying clouds can more easily move around an isolated peak, rather than being pushed up over it. You may see an undercast from peaks along ridges, but often the cloud deck will be only to one direction because the clouds get blocked by the terrain. Camel’s Hump saw several days in a row of stellar undercast conditions the first few weeks of January. Mt. Mansfield and Mt. Hunger are other favorites of Stephanie and Ted.

Wherever you go, it’s crucial you’re familiar with your hike and planned route. Since the best chance of seeing an undercast is at sunrise, you’ll need to hike in the dark and cold. Always give yourself plenty of time to reach your target viewpoint, considering hiking in winter is slower going and you may need to break trail through fresh snow. Proper layers, lighting, and warm gear will make you safer and more comfortable, especially as you wait around on an unprotected summit for the sun to rise.

Use all the tools at your disposal

As Ted says, “The weather patterns that cause these often aren’t particularly remarkable.” So, start cluing yourself in on the real-life elements that might stack up for an especially promising forecast. Stephanie checks social media photos often to watch for patterns and locations that frequently see undercast conditions. They check mountain webcams like the one at Mt. Washington Observatory and Whiteface in the Adirondacks. This helps them confirm their predictions, especially on days when they can’t get out and hike themselves. And get used to looking out the window often, recognizing low, uniform cloud layers at home as possible conditions for an undercast at higher elevations.

Make the most of it

There’s no perfect science to catching an undercast, Ted and Stephanie both stress. You might find yourself in the cloud layer, rather than above it. Having the right mindset and enjoying the journey will go a long way.

If you do manage to hit just the right conditions, Stephanie, an adventure and elopement photographer, has a few tips for capturing the moment. Aim for golden hour — the hour or two after sunrise and before sunset — when the sun is low in the sky and casts a flattering glow on all subjects. Even novice photographers will catch the rich colors as they play off the clouds below. Arrive at least 20-40 minutes before the sun breaks the horizon to see the sky blaze pink, purple, and orange when thin, higher clouds are also present. Pack those extra layers and hang out for a while to watch the light change as the sun moves higher. If you’re willing, trek up a lightweight tripod to stabilize your shots. Remember to walk only on the rocks in alpine zones as you maneuver around the summit to capture the incredible view.

Read more about Stephanie and Ted’s undercast hunting on Stephanie’s Adventure Blog post “Sunrise on Camel’s Hump.” Follow along on Instagram @greatrangeframes.

Have you seen a dazzling undercast in the Green Mountains? Send us a photo — along with location, time of year, and time of day if you can — to [email protected]. We’ll reshare our favorites.

[…] of the Escarpment let me escape the dreary conditions below. I was gazing out over a sea of undercast, one of the most surreal weather phenomena in the world, in my humble opinion. A sheet of white […]