This article was written by Vic Henningsen and previously appeared in the Summer 2020 Long Trail News. Historian Vic Henningsen was a caretaker and ranger-naturalist on Mount Mansfield in the 1970s. He thanks Larry Van Meter and Peter A. Gilbert for their help with this article.

It’s not clear who first hiked the whole Long Trail, but we do know who wanted to be first, claimed to be first, and, if we’re willing to accept a significant route variation, might in fact have been first.

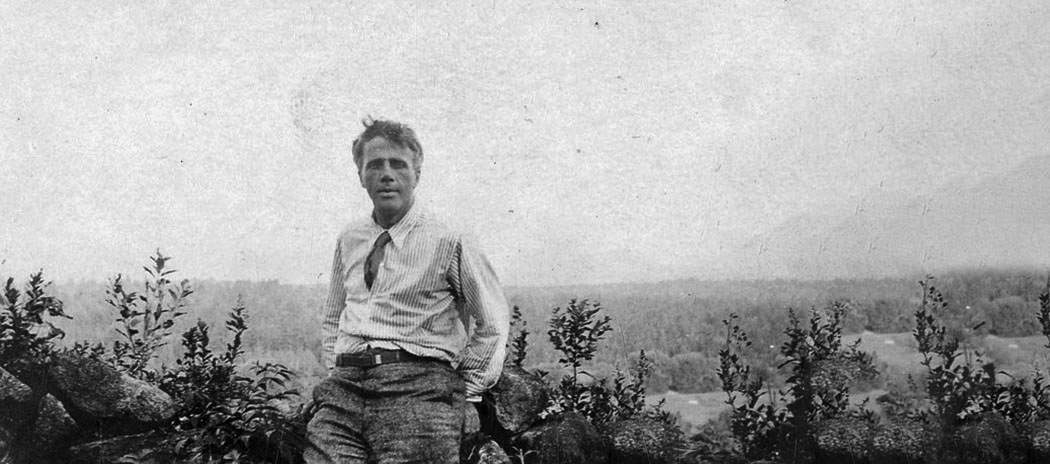

That would be a party of young people who in 1922 sought to become the first family group to end-to-end the trail, which at that time ran from Massachusetts to the Lamoille River at Johnson. Their leader was 23-year-old Lesley Frost, an exuberant young resident of South Shaftsbury who recruited her brother, Carol; her younger sister Marjorie; and Marjorie’s friend Lillian LaBatt to undertake what became an 18-day late summer journey. Lesley also enlisted her father, Robert Frost.

Yes, that Robert Frost.

A tireless walker and botanist, Frost had delighted in introducing his children to the natural world, taking them with him on walks and encouraging them to seek new discoveries by quoting from Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner: “We were the first to ever burst into the silent sea.” Before moving to Vermont from Franconia, New Hampshire, the Frosts regularly climbed local peaks like Lafayette, the Kinsmans, and Moosilauke. When Lesley broached the idea of the Long Trail, Frost jumped at the opportunity. He was 48, his children were reaching adulthood—who knew when there’d be another chance to spend so much time together outdoors?

But Frost was also weary and preoccupied. Recognition as a poet had come relatively late—in his forties—and he had to scramble to make ends meet, spending most of his time on the road giving readings and lectures, and serving as a visiting professor. During the 1921-1922 academic year, he had been a visiting fellow at the University of Michigan, returning to Vermont worn out in late June.

He remained immensely creative, spending an entire July night writing a draft of his 413-line poem, “New Hampshire,” and then, at dawn, crafting his masterwork “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” in one sitting. But Frost was tired and out of shape when the group embarked in the early morning hours of Tuesday, August 15. Worse, he was wearing a new pair of walking shoes that pinched. He’d intended to break them in more thoroughly, but hadn’t had time.

At departure, the group now included Edward Richards, a student friend of Frost’s. Frost’s wife Elinor and third daughter Irma opted to skip the family trip. Leaving from their South Shaftsbury front yard, they spent their first day bushwhacking over East and Bald Mountains before reaching the Long Trail at Hell Hollow Camp south of Glastenbury Mountain. This, Lesley argued in her trip report, was the equivalent of starting at the Massachusetts state line, also a day’s walk away.

Days on the trail began well for Robert Frost. Biographer Lawrance Thompson provides a lyrical view of the poet’s mode of travel:

“[H]e was the only one who settled into a slow and deliberate pace, content to let his children and their companions romp ahead. His private notions of mountain-climbing were based not so much on the fable of the tortoise and the hare as on his pleasure botanizing with eyes and fingers and nose, as he went. He treated both sides of the path as though they were pages of an open book, as though he were there to read both pages as he walked… All these casual observations made mountain-climbing a special form of luxury for him. His lingering as he walked was merely a part of his cherishing.”

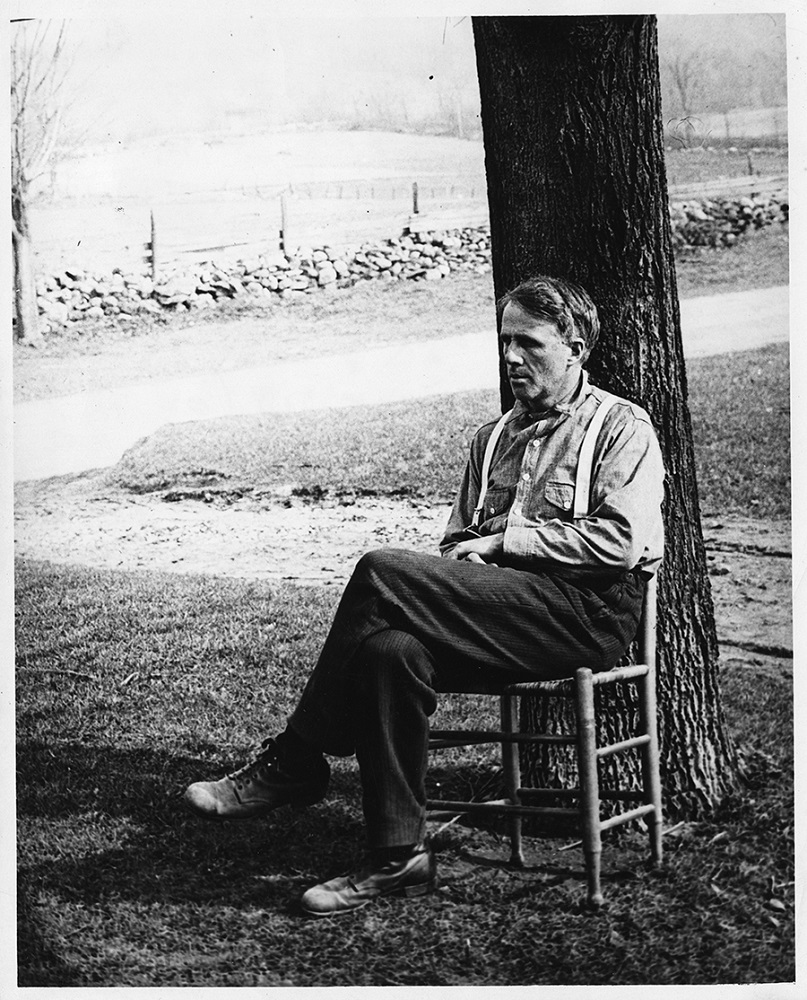

But joy soon gave way to trouble. Tight new shoes damaged his feet and, despite cutting them open to give his toes more room, Frost found his hike becoming slower and slower, and more and more painful. At the end of the fourth day, just short of Bromley Mountain, the group sheltered from a heavy thunderstorm at a local inn. Frost convinced them to stay two nights to see if his feet might recover sufficiently to permit him to continue.

It didn’t work, so Frost left the trail accompanied by his friend Richards, who had had enough and headed home. Frost promised his children he’d take a few days off, get a new pair of shoes, and meet them again at Lake Pleiad in Middlebury Gap. Interestingly, he didn’t return to South Shaftsbury, apparently because he didn’t want to face his wife and confess that overconfidence had brought him low. Instead, he traveled to Rutland, bought a pair of sneakers, and slowly made his way to Middlebury Gap, where he rendezvoused with the group (now calling itself “The Big Four”) as promised, six days after parting.

Back on the trail it soon became clear that new sneakers and several days of rest were insufficient for Frost, who was now having knee trouble as well. Unable to maintain the pace set by his children, he again abandoned the trip, this time for good. He told the rest he would find his way to Franconia, New Hampshire, where he and his wife would spend part of September.

Precisely where he quit the trail remains unclear. Years later he told biographer Thompson he left at Lincoln Gap, but Lesley’s account, written shortly after the trip, says he made it as far as Montclair Glen.

Either way, he didn’t go to Franconia—at least not right away. He told Thompson he realized that by following the comparatively flat “Valley Road” (now Vermont Route 100) he could keep pace with his children on the high ground to the west, so he decided to surprise them at the end of their trip. For several days Frost slowly walked north, sleeping in fields and barns, eating in roadside cafes or farmhouse kitchens. But, nearing the Lamoille River, he realized that the Big Four were traveling so fast he would still probably miss them. He resolved to catch a train to Franconia.

By now he was a complete mess: ragged, dirty, unshaven, and still nursing sore feet, which troubled him so much that he was wearing one sneaker and one carpet slipper he’d picked up along the way. As Frost boarded the train a conductor attempted to eject him. He was saved by the intervention of another passenger, an English professor from Georgia, who got the shock of his life when he learned the identity of the tramp he had protected.

The Big Four indeed finished before Frost could catch them—225 miles in 17 days of walking. “We carried rather light packs,” Lesley wrote later, “varying in weight from fifteen to thirty pounds. But,” she went on:

“[T]here is no point in carrying greater weight than is absolutely necessary. We carried two blankets, a heavy sweater, and a poncho apiece. More blankets would have been a comfort, though it would have taken ten blankets, and quilts at that, to have suited me. As for food, we avoided canned goods, which we found those we met carrying in abundance. Our supply consisted mostly of bread, butter, eggs, shredded wheat, raisins, crackers, rice and sugar and then various things, such as cookies and candy, that we consumed within a day or so of market.”

The Long Trail then was quite different in many respects from today’s route, particularly in the south, where it avoided Glastenbury and Stratton Mountains, and Bourne and Little Rock Ponds, for example. It had long lost campsites like Somerset Bridge south of Stratton, Three Shanties near Griffith Lake, and Buffum Camp between White Rocks and Clarendon Gorge.

But Lesley’s report also records stops familiar now, and comments that could have been written recently: “We’ll remember the pancakes and the maple syrup and the sunset” at Glen Ellen, for example; or “Twenty of us slept in bunks built for twelve” at Montclair Glen; and “a night of sleeplessness” at perpetually overcrowded Taft Lodge. With mostly fair skies, no bugs, few porcupines, and lots of blueberries to pick as they walked, it was, said Lesley, “a pleasure to accomplish.”

Lesley and her compatriots never contacted the Green Mountain Club for official confirmation that they were first to end-to-end the Long Trail. If they had, the claim might have been challenged because they hadn’t followed the trail from the Massachusetts line to Hell Hollow. It didn’t seem to matter to most people: Lesley submitted a report of the trip to the Bennington Banner, which published it on September 12, 1922, under the front-page headline:

Long Trail, 225

Miles, Yields to

Youth and Vigor

Entire Length Traversed in One

Continuous Hike

THE FIRST TIME ON RECORD

Let the experts quibble—as far as the Big Four were concerned, they were first.

Things were more complicated for Robert Frost. His determined attempt to complete as much of the trip as he could demonstrated an extreme reluctance to quit. His unwillingness to return to his wife in South Shaftsbury—preferring to meet her in Franconia as originally planned—suggests significant embarrassment at falling short of his goal.

Indeed, he never fully explained what happened—then or later. Writing to friends after the event, he claimed to have completed 115 miles, 125 miles, or “something like 200 miles”—depending on whom he was writing and, apparently, how much that person might believe. It seems the further away his correspondent, the more mileage Frost claimed.

But the letters illustrate another truth, familiar to enthusiastic hikers ultimately slowed by the wear and tear of age: Robert Frost was no longer in charge. Indeed, on this trip his children were looking after him—slowing down to allow him to keep up, and taking time off to see if his ailments would ease.

To one friend he wrote:

“I should admit that the kids did all two hundred and twenty miles. I let them leave me behind for a poor old father who could once out-walk, out-run, and out-talk them but can now no more.”

To another he expressed good-humored acceptance:

“I am beginning to slip: I may as well admit it gracefully and accept my dismissal to the minor and bush leagues where no doubt I have several years of useful service still before me as pinch hitter and slow coach.”

But to a third he revealed lingering reluctance to yield the spotlight, writing of Lesley’s trip report:

“I don’t feel that it does me personally any justice… When I dropped in my tracks [and left the trail] I was gone through for what money I had in my pockets that might be useful to the expedition and then left for no good… You’ll notice nothing more is said of me.

I’m sorry to have to admit that the Green Mountain Expedition was a success without me.”

Yet his letters also gave voice to admiration, even pride:

“Those children though! Too much cannot be said for their grim forging. They had done their two hundred in fifteen consecutive days when they left me for a pitiable. May their deeds be remembered.”

The Frost Long Trail adventure marked a kind of coming of age for all concerned, highlighted by Robert’s recognition of his children’s emergence as adult individuals, reinforced when Carol Frost and Lillian LaBatt became engaged during the trip. It would also signal the start of the scattering of the family. Memories of the hike became poignant in later years, after Marjorie died in childbirth and Carol committed suicide, as a moment when the family shone most brightly.

Though Frost remained an inveterate walker all his life, we read of no further major mountain hikes, let alone long-distance backpacking trips. The Long Trail venture seems to have been the end of at least one path for Robert Frost.

But then again, maybe not. Some two weeks after the journey, he offered his most detailed assessment of what it meant to him:

“I came back from Michigan University all puffed out with self-hate that would have curdled the ink in my pen… There was nothing for it but to get away from myself. You know they say there is no such thing as leaving ourselves behind: and they are right if they mean by railroad by automobile by airplane or by horse. But if we will do it on foot at a walk not at a run – at a walk deliberately, not thinking as we go so much as entertaining fantasies, it is another matter that few nowadays have heard anything about: the escape from self is complete.”

The Sound of Trees

BY ROBERT FROST (1874-1963)

I wonder about the trees.

Why do we wish to bear

Forever the noise of these

More than another noise

So close to our dwelling place?

We suffer them by the day

Till we lose all measure of pace,

And fixity in our joys,

And acquire a listening air.

They are that that talks of going

But never gets away;

And that talks no less for knowing,

As it grows wiser and older,

That now it means to stay.

My feet tug at the floor

And my head sways to my shoulder

Sometimes when I watch trees sway,

From the window or the door.

I shall set forth for somewhere,

I shall make the reckless choice

Some day when they are in voice

And tossing so as to scare

The white clouds over them on.

I shall have less to say,

But I shall be gone.

Used with the permission of the Robert Frost Copyright Trust.

This was a lovely way to spend some time on this early Sunday morning. Being a hiker is such an individual thing. Most days when I hike I always bring a dog and always always comfortable shoes!! Bad shoes are the death of a hiker!

We’re glad you enjoyed the article! We definitely feel for Frost and his boot problems!