This article was written by Vic Henningsen and previously appeared in the Spring 2019 Long Trail News.

Green Mountain Club caretakers are a familiar sight to those visiting the busiest parts of the Long Trail, but few hikers know we owe their presence to the hard work of visionaries more than a half century ago.

In the mid-1960s University of Vermont botany professor Hubert “Hub” Vogelmann oversaw research on Camel’s Hump that would bring national attention to the degradation of fragile ridgelines and mountaintops. Vogelmann and his students focused on acid rain, ultimately influencing state and federal environmental policy, but they also noted damage to delicate ecological communities caused by rapidly increasing number of visitors. Similar studies in the Adirondacks and White Mountains confirmed that popular peaks were in danger of being “loved to death” by enthusiastic but uninformed visitors.

In the summer of 1968, some 20 Long Trail miles to the north, Burlington Section member and passionate environmentalist Ken Boyd volunteered part-time as caretaker at Bolton Lodge. Beginning in the 1920s the GMC had stationed caretakers at Stratton Pond, Killington, Camel’s Hump, and Mount Mansfield, maintaining shelters, supplying firewood, and providing blankets and occasional meals to weary hikers. The early club caretaker program lapsed in the quiet years after World War II.

When Boyd arrived at Bolton, his aims were quite different. Like Vogelmann, he knew the Green Mountains were besieged by human activity that threatened to overwhelm what visitors sought to enjoy. While Vogelmann and his students collected data on rainfall, soil erosion, and plant damage, Boyd began to study backcountry users. He made a point of talking with everyone who passed through, kept meticulous usage records, and amassed data on trail and shelter conditions along much of the Long Trail. Hiker reports confirmed his suspicion that the trail system needed more thoughtful management.

Boyd developed a strategy of changing hiker behavior through low key, face to face education. Rather than harassing visitors about littering, he packed out the Bolton dump, explained the basic principles of what became the pack-it-in, pack-it-out philosophy, and enlisted hikers as partners to respect the trail, shelters, and mountain environment.

Visitors didn’t intend to damage the resource, he believed; damage came from lack of knowledge, not malice. So, he concluded, don’t treat them like criminals, and don’t make them feel like idiots. In a friendly conversational approach, he explained what he was doing and why, and why they might want to join in. If it worked, they might influence others. It might be slow, but it promised to be effective.

As the visitor tide rose in that decade, Vogelmann and Boyd pushed for action. Concerned also about Camel’s Hump’s even more heavily traveled northern neighbor, Mount Mansfield, Vogelmann pressed UVM (which owned most of Mansfield’s alpine area) and the Vermont Department of Forests and Parks, as it was then known, (which managed it) to mitigate the damage. Meanwhile, using statistics he had compiled at Bolton, Boyd lobbied the Burlington Section to reestablish shelter caretakers on Mount Mansfield.

In 1969, Vogelmann found an ally in Vermont State Parks Director Rodney Barber, a master diplomat and administrator. He brokered a complicated agreement by UVM, the Mount Mansfield Company, and the Department of Forests and Parks to support a ranger on the Mansfield ridge. The same year, Boyd’s data-driven campaign convinced the Burlington Section to station the first caretaker at Taft Lodge since 1946.

Starting in June 1969, state ranger-naturalists on the ridge and GMC caretakers at Taft did what they could to cope with hordes of visitors, whose numbers continued to increase because of a nationwide backpacking boom further swelled by widely disseminated articles in local and national news media publicizing the Long Trail and Mount Mansfield. It was slow and often deeply frustrating work.

But things were beginning to change. In October 1969, prominent activists and stakeholders organized the Green Mountain Profile Committee to marshal a coordinated, ecologically driven approach to resource preservation. Vogelmann chaired this group, but always credited its development and influence to GMC president Shirley Strong, whom he later described to historians Laura and Guy Waterman as “the driving force” in pulling the State of Vermont, the GMC, UVM, and others into effective partnership.

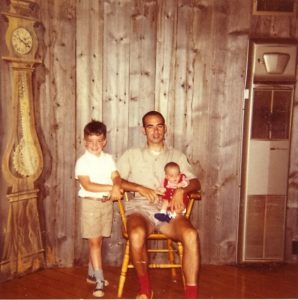

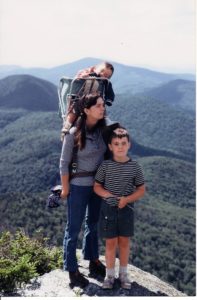

By 1971, this began to pay off. Now the GMC’s volunteer caretaker coordinator, Ken Boyd persuaded the club to expand coverage beyond Taft Lodge to Butler, Taylor, Bolton, Gorham, and Montclair Glen Lodges, and Stratton Pond. Perhaps most importantly, Rodney Barber appointed Ken Chief Ranger-Naturalist on Mount Mansfield. Ken and his wife, Alice, who acted as a full member of the ranger-caretaker team, moved into the Mount Mansfield Company’s Octagon building with their two young sons, John and the newborn Jasen.

Their arrival marked a crucial moment. The state ranger-naturalists and GMC caretakers could easily have descended into rivalry, but they united under the leadership of the Boyds. Alice’s managerial and logistical skills complemented Ken’s energy and drive as they showed enthusiastic young rangers and caretakers how to implement on a much larger scale the low key educational approach that Ken had developed at Bolton Lodge.

By Labor Day weekend 1971, the pattern that defines Vermont’s approach to backcountry management was set. The club caretaker system absorbed the state’s ranger-naturalist program in 1975. Since then, Long Trail hikers have continued to receive a consistent message from all backcountry personnel via friendly explanation and persuasion rather than enforcement.

This “Green Mountain model” was widely adopted elsewhere. Today Appalachian Trail thru-hikers and visitors to major summits in the White Mountains and the Adirondacks regularly encounter trail stewards whose approach mirrors that originated by GMC caretakers a half century ago.

Hub Vogelmann, Shirley Strong, and Rod Barber laid the groundwork for a united effort to preserve the fragile ecosystem of Vermont’s mountain ridgelines. But Ken and Alice Boyd and the rangers and caretakers they inspired and led invented and implemented the strategy that made that effort successful. Two generations later the ripple effect of the caretakers’ low key “each-one-teach-one” outreach to mountain visitors continues to spread.

Historian and Vermont Public Radio commentator Vic Henningsen was a caretaker and ranger-naturalist on Mount Mansfield during the 1970s. He would like to thank Alice and Ken Boyd, Howard Van Benthuysen, and Larry Van Meter for their help with this article.

[…] we celebrate 50 years of the Green Mountain Club caretaker program, it’s worth recognizing the amount of effort required to keep the Long Trail System tidy. Same as […]