This article was written by Preston Bristow and originally appeared in the Fall 2014 Long Trail News. Preston Bristow is a past President of the Green Mountain Club whose varied career includes implementing the land protection effort for the Appalachian Trail in Vermont and directing the Vermont Land Trust’s conservation easement stewardship program. He has a lifelong interest in all things rail. Join Preston in his Taylor Series talks to learn more about the Long Trail and logging railroads – on Saturday, Februrary 9th, in Manchester, or on Friday, April 26th, in Norwich.

Green Mountain logging railroads lacked the grand scale of those in the Adirondacks, where twenty-two railroads reached deep to extract old growth forests. And railway loggers in the Green Mountains also lacked the flamboyance of the White Mountains’ J.E. Henry, timber baron of the Pemigewasset Valley and Zealand Notch. “I never see the tree yit that didn’t mean a damned sight more to me goin’ under the saw than it did standin’ on a mountain,” Henry famously proclaimed.

But the Green Mountains did have logging railroads, and at various times the Long Trail followed parts of them.

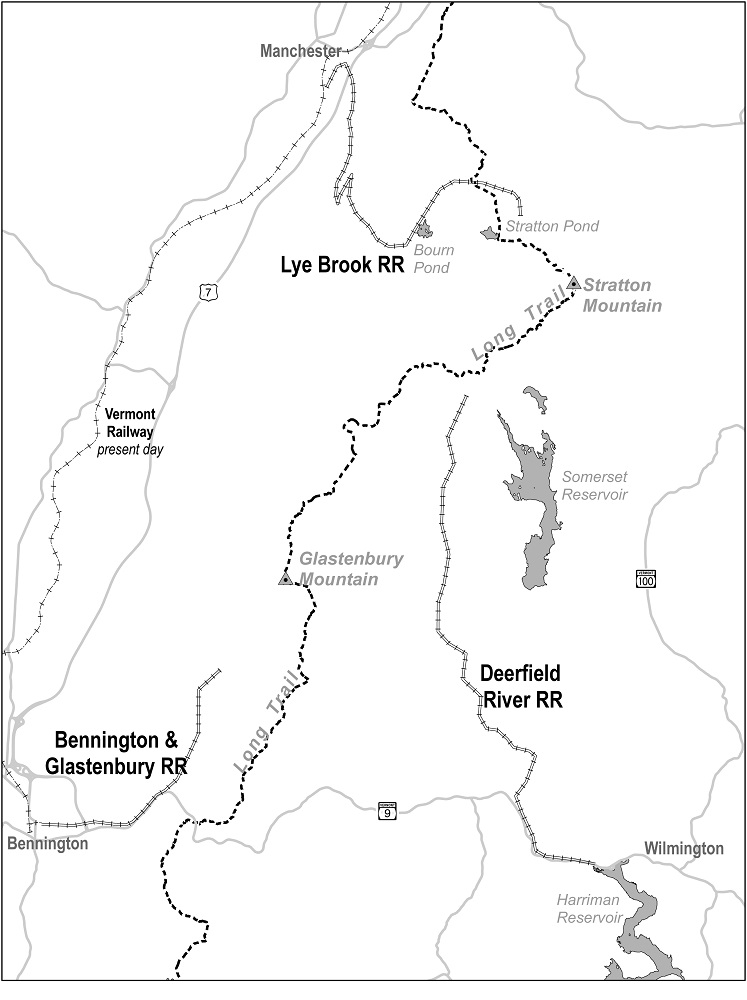

When Lee Allen and I were caretakers in 1973 and 1974 (see Trail Tales: Musings from Two Long-Ago Stratton Pond Caretakers, LTN Summer 2013), little did we imagine there had been not one but two logging railroads within a few miles of the pond. And a third logging railroad had operated near Bennington.

My first revelation came with the publication of The Coming of the Train, Volume I in 2008 by Brian Donelson. Chronicling the Hoosac Tunnel & Wilmington Railroad, it included a chapter on the Deerfield River Railroad, which extended from Wilmington north through Searsburg and Somerset into the south side of the town of Stratton. (The Coming of the Train, Volume II, published in 2011, had much more on the Deerfield River Railroad.)

Donelson’s first book whetted my appetite for mountain railway history. I then learned of the Rich Lumber Company and its Lye Brook Railroad, which climbed a wicked grade out of Manchester up Lye Brook Hollow to Bourn Pond and east into the town of Winhall north of Stratton Pond. The company and its railroad are documented in a chapter by William Gove in Rails of the North Woods, published in 1978.

Finally, a third, mostly forgotten logging railway, the Bennington & Glastenbury Railroad, went un-chronicled until Tyler Resch published Glastenbury: The History of a Vermont Ghost Town, in 2008. This rail line extended nine miles from Bennington through Woodford Hollow and up Bolles Brook to a logging settlement in the town of Glastenbury at “The Forks” of the brook. Although these three railroads were abandoned nearly a century ago, their stories went largely untold until recently.

Bennington & Glastenbury Railroad

The first abandoned logging grade used by the Long Trail was the Bennington & Glastenbury. The 1917 first edition of the Long Trail Guide describes an alternative route as follows: “The optional route from G.M.C. camp at Hell Hollow follows Glastenbury stream about 1½ miles then along old railroad track to Old Glastenbury, 1½ miles further. (Look out for bad holes in track.)” This “optional route” was described until the sixth edition (1924) of the Guide, when it was downgraded to a side trail. Then, in the eighth edition (1930) of the Guide, following a major relocation, it became the main route of the Long Trail. It remained the main route until the twentieth edition (1971) of the Guide, after which it was abandoned following another major relocation. All told, this one-and-a-half mile stretch of railroad bed served seven years as an optional route, six years as a side trail, and forty-one years as the main route of the Long Trail!

The story of the Bennington & Glastenbury Railroad is fascinating. It was built in 1873 as a logging railroad, and continued twenty-two years until 1889, when the trees were gone. In 1895 the Bennington & Woodford Electric Railway Company resurrected it as a trolley line. The logging settlement of Glastenbury at the end of the line became an upscale resort with hotel, clubhouse, dance hall, dining room and casino.

Alas, the trolley line was irreparably damaged in the “freshet” (flood) of 1898, and the resort was abandoned, no doubt a great loss to its investors. The seventeenth edition (1963) of the Guide refers to this when it describes the trail as following “the grade of a former lumber railroad (later a trolley line) which extended from Bennington into this valley.” The railway had been abandoned for sixteen years when this route of the Long Trail was first blazed in 1914.

The end of the line for this railroad and the location of the logging settlement (later resort) of Glastenbury can be seen on the Division 2 map of the current Long Trail Guide. Look approximately one inch south of the Glastenbury Mountain summit to where Bolles Brook splits (still called “the Forks” by many locals). Foundation bricks remain there, and some railway hardware lingers in the bushes along the old roadbed.

Deerfield River Railroad

The Deerfield River Railroad was the second abandoned logging railroad grade used by the Long Trail. According to the Guide, the original route of the trail followed “practically level country” along woods roads from Somerset Dam to Grout Job (near Grout Pond). Abandonment of the northernmost portion of the Deerfield River Railroad in 1919 offered a more interesting route along the Deerfield River. The second edition (1920) of the Guide has the Long Trail following a three-mile stretch of the newly abandoned railway. It remained there for ten years until the eighth edition (1930) of the Guide, when a major relocation moved the trail to its present ridgeline route north of Glastenbury Mountain.

The Deerfield River Railroad, although primarily a logging railroad, was chartered by the State of Vermont as a common carrier. Amos Blandin, its founder, envisioned his railroad extending to Manchester and continuing to carry freight and passengers after the logging was done. However, the railroad succumbed to the growing need for electric power. In 1920 it was purchased by a subsidiary of the New England Power Company. Railway operations ceased in 1921, and by 1923 the railroad’s base of operations at Mountain Mills was submerged under the power company’s new Harriman Reservoir.

No one is quite sure of the Deerfield River Railroad’s end point. An early document called for the northern terminus to be “a point at or near the east bank of Bourn Pond,” but it appears the rail line never reached quite as far as the Stratton-Arlington Road, also known as the Kelly Stand Road. The 1920-1930 route of the Long Trail over the Deerfield River railway can be traced on the Division 2 map of the current Long Trail Guide. It began at a point east of Story Spring Shelter on a road identified as “USFS 71” and followed the Deerfield River south for about two inches (three miles).

Lye Brook Railroad

The third abandoned logging railroad grade used by the Long Trail was the Lye Brook Railroad. Originally the trail extended north directly from Stratton Mountain to Prospect Rock, bypassing Stratton and Bourn Ponds altogether. The fourth (1922) edition of the Guide, however, offers this tantalizing alternative: “The Trail emerges from dense second growth to a large clearing with the remains of a railroad. This may be followed west (not marked) to Bourn Pond by always following uphill; the roadbed makes many wide serpentine curves and crosses some ravines by bridges of huge logs.”

By the sixth (1924) edition of the Guide the Long Trail was routed past both Bourn and Stratton Ponds. North of Bourn Pond the trail followed three miles of a different branch of the Lye Brook Railroad than the one described above. The Long Trail followed this branch railroad for fifty-four years, until the twenty-first (1978) edition of the Guide, when a major relocation left Bourn Pond off the Long Trail.

Flush from railway logging near the Adirondacks’ Cranberry Lake, the Rich Lumber Company bought the timber on what they thought was a 12,000-acre tract on the East Mountain plateau (where Bourn and Stratton Ponds are located), built a sawmill in Manchester, and pushed a railroad up through Lye Brook Hollow. Immigrant workers literally carved the rail bed into the side of the hollow, and avoiding a grade of more than six percent required a switchback about half-way up. The railroad began operations in 1914, but by 1919 the timber supply ran out. The 12,000 acres turned out to be 7,500 acres, so rail operations came to a premature end. The Rich Lumber Company was liquidated in 1920.

The fifty-four-year route of the Long Trail over the rail bed of the Lye Brook Railroad can easily be walked today. It is the stretch of the Branch Pond Trail that extends from Bourn Pond north to William B. Douglas Shelter.

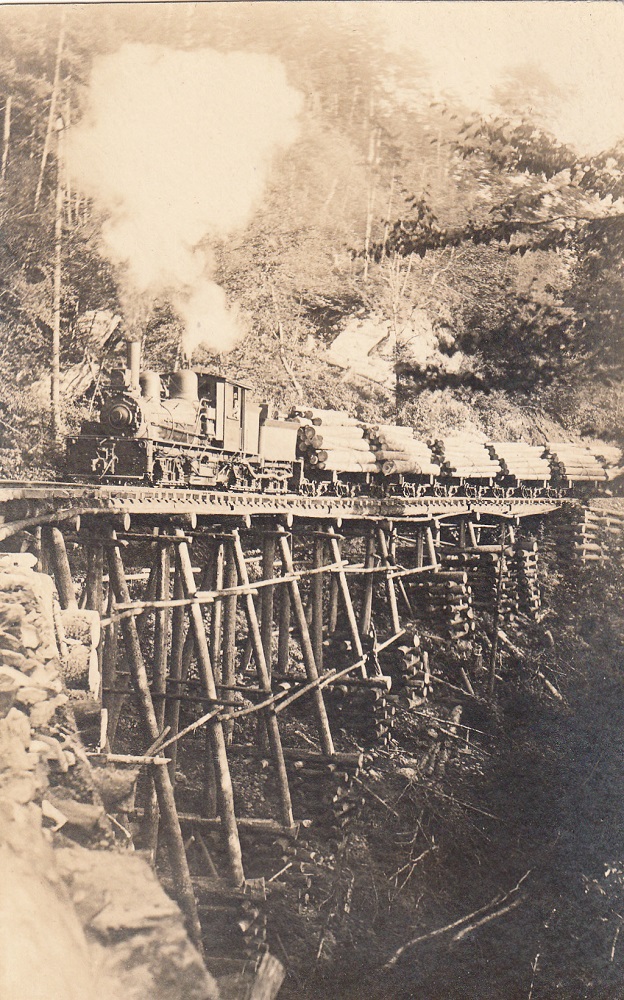

Parts of the lower portion of the Lye Brook Trail follows the main line of the Lye Brook Railroad (other parts follow a logging truck road dating to the 1950s). The spur 2.3 miles up the Lye Brook Trail leading to Lye Brook Falls also follows one switchback of the main line. The railroad crossed the brook just below the waterfall on a high timber trestle. Look for cinders left by coal burning locomotives along the roadbed; a few ties also remain. The Branch Pond Trail also follows part of the Lye Brook Railroad network as it approaches Bourn Pond.

Lee Allen and I have found several large piles of bricks about two miles north of Stratton Pond near the current Long Trail that we believe were former charcoal kilns alongside yet another branch of the Lye Brook Railroad.

First Rail-to-Trail

Was the Green Mountain Club’s early use of abandoned logging railways the first “rail-to-trail” in the nation? As usual, the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC) has us beat. According to the first (1907) edition of the White Mountain Guide, a trail into Zealand Notch following the abandoned Zealand Valley Railroad was blazed by the AMC in 1906, some eight years before the abandoned Bennington & Glastonbury Railroad was blazed by the GMC in 1914.

It may seem incongruous that something as massive and industrial as a railroad would be located in federally designated Wilderness areas of the Green Mountain National Forest. Yet it does make sense. Only the most remote areas that could not be feasibly reached by other means were logged by railroad.

Today, these three logging railways have left little trace. It was much cheaper to build log trestles or bridges to span ravines and swampy areas than to cut and fill, and those structures are long gone. The rails and spikes were also pulled when the lines were abandoned. Lee Allen and I have traced some of these railroad lines, and with the exception of the Bennington & Glastenbury found them very difficult to follow.

The public hue and cry after the stripping of White Mountain and Adirondack forests led to the establishment of the White Mountain National Forest and Adirondack Park. Vermont’s logging railroads caused less consternation. Early Long Trail Guide descriptions suggest that GMC trailblazers stumbled upon these abandoned rail lines without knowing much about them, or being much interested in them.

No, Vermont’s logging railroads were neither grand nor flamboyant, but they got the job done. A colorful part of the Long Trail’s history, their stories are worth knowing, and their moldering roadbeds still call to adventurous hikers and bushwhackers.

Rails over Killington?

During the railway mania of the 1840s, a transcontinental railroad connecting the deepwater harbor at Portland, Maine, with Chicago and the Pacific Coast was proposed. The most direct route across Vermont was surveyed, and the Vermont Legislature granted a charter in 1847. This ambitious line would have crested the Green Mountain divide at an elevation of 1,951 feet through The Elbow, a gap 3.3 miles north of Sherburne Pass.

Fundraising for the railroad faltered during the Civil War, but post-war optimism was so strong that the route is depicted as reality on the Beers Atlas of 1869. The only Vermont portion to be built was the 14-mile long Woodstock Railroad, which was abandoned in 1933. (U.S. Route 4 crosses Quechee Gorge on one of the railroad’s bridges.)

Imagine locomotives shattering the tranquility of the forest as they thunder up to the gap the next time you cross Elbow Road between Tucker-Johnson and Rolston Rest Shelters!

Vermont’s Rail Trails Today

Here are Vermont’s rail trails of today, including a quarter-mile stretch followed by the Long Trail!

- Alburg Rail Trail (3.5 miles) in Alburg

- Beebe Spur Rail Trail (4 miles) parallels Lake Memphremagog in Newport

- D&H Rail Trail: North Section (9.2 miles) in Castleton and Poultney; South Section (10.6 miles) in Pawlet and Rupert

- Island Line Rail Trail (14 miles) from Burlington to South Hero; features a spectacular route over Lake Champlain on a causeway

- Lamoille Valley Rail Trail (93 miles) from Swanton to St. Johnsbury (right-of-way owned but trail not yet completed); followed by the Long Trail for one-quarter mile in Johnson

- Missisquoi Valley Rail Trail (26.4 miles) between St. Albans and Richford

- Montpelier & Wells River Rail Trail: East Montpelier to Plainfield (2 miles); Groton to Marshfield (18 miles); Boltonville to Wells River (1.8 miles)

- Toonerville Rail Trail (3 miles) from Springfield to Charlestown, N.H.

- West River Rail Trail: Upper Section (12.5 miles) between South Londonderry and East Jamaica; Lower Section (3.5 miles) in Brattleboro and Dummerston

- Also, about 13 miles of Sections 1 and 2 of the Catamount Trail follow the former Hoosac Tunnel & Wilmington Railroad, and about 3 miles of Section 3 follow the former Deerfield River Railroad.

Leave a Reply