Daan Zwick was a Green Mountain Club caretaker in the 1930s, an active volunteer into the 1980s, and a generous supporter of the club. After a full and active life, he died on November 21st at his home in Rochester, New York. Daan was 97 years old.

Daan’s deep commitment to the Long Trail motivated him to financially support some of the club’s most significant projects, including the Long Trail relocation through the Winooski River Valley and construction of the Winooski River Suspension Bridge. Daan’s support also enabled us to restore Taft Lodge on Mount Mansfield and build field staff housing behind club headquarters, today called The Back Forty.

But probably Daan’s greatest impact was in the example he set for generations of Green Mountain Club field staff. A Burlington, Vermont, native, Daan developed a love for the outdoors and the Trail through outings with his family and the Boy Scouts. He became the first Taylor Lodge caretaker, at age 15, and continued to care for the trail and shelters for decades to come. When Daan was no longer able to hike, he stayed connected to the club from afar through his philanthropy, written stories, and friendships made with GMC members and volunteers.

Daan was a GMC pioneer whose spirit will remain in the walls of The Back Forty, Taft and Taylor Lodges, on the planks of the Winooski River Bridge, and in the hearts of all who were fortunate to know him.

Each time I think of Daan walking across the newly completed Winooski River footbridge—with trekking poles held high—on that snowy day in December 2014, a smile is brought to my face.

Dann’s joyful exuberance and passion for the outdoors will be missed. We extend our sincerest condolences to his family and friends.

Daan was a thoughtful storyteller and it seems appropriate to share the story of his summer as the first caretaker at Taylor Lodge in 1938, written in his own words. He submitted this memoir to GMC in December 1997 and it previously appeared in the Spring 2017 Long Trail News.

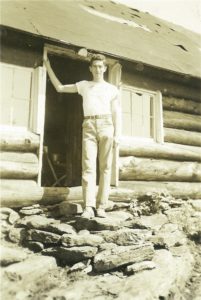

A Memoir from 1938 Taylor Lodge Caretaker Daan Zwick

In 1938 Taylor Lodge was a beautiful log cabin, snugly situated east of the Long Trail where it descended into Nebraska Notch. The Burlington Section built it in 1926 as a memorial to James P. Taylor, founder of the Green Mountain Club.

A century earlier the notch had been a route for wagon travel and other communication among the inhabitants of Mansfield, a township straddling the Green Mountain range. The traverse was not an easy journey, particularly in March, when farmers on the west side had to cross over to participate in the annual town meeting. This difficulty led to the demise of the Town of Mansfield, which voted to split and become Underhill on the west and Stowe on the east.

By 1938 that ancient route was barely recognizable as an old lumbering road, dropping to Lake Mansfield on the east and to the trailhead at Stevensville on the west. Vestiges of the more recent past were many cords of split chestnut neatly stacked along the trail, an effort by the Civilian Conservation Corps to salvage something from the devastation of the chestnut blight. So far as I know, this wood was never used. The stacks just rotted away.

The logs of Taylor Lodge also had trouble surviving, but they did not rot away. The original lodge lasted just a quarter of a century, burned down by careless campers in the winter of 1950. Its replacement, a similar log cabin built again by the Burlington Section, survived another quarter-century, burning in 1977. In 1978 the Burlington Section replaced it with a different, non-log structure, having an open front, and no stove inside. The only change I have observed since then is on paper—the 1996 guidebook now recognizes that its capacity is 15 campers, rather than the 20 advertised in previous guidebooks.

Caretakers were stationed at Taft Lodge, seven miles north on Mount Mansfield, since the 1920s. Butler Lodge, three-and-a-half miles closer and built in 1933, acquired its first caretaker in 1937. Usually teachers or college lads, these caretakers were hired and supervised by the Burlington Section. So I was surprised when Larry Dean asked me early in 1938 if I would like to take such a job at Taylor, for I was only fifteen, just finishing my junior year at Burlington High School. Larry, in charge of the four cabins on the Burlington Section, was my Scoutmaster, so he knew of my love for the out-of-doors and the mountains. I was proud that he had that much confidence in me, so, with my parents’ permission, I quickly accepted the position of the first-ever caretaker at Taylor Lodge.

As soon as school was out at the end of June I assembled my camping gear, bought a lot of food that would keep without refrigeration, and got a ride with my father to the trailhead at Stevensville. I used my Trapper Nelson pack frame (bought because that’s what Larry always used) to carry in the big boxes of supplies, and my father helped me by taking in a load in his Bergen “Monsterbasket,” a rucksack he prized. I was pleased when he left it with me, for it was useful on hikes, particularly my weekly trips to a farm near the trailhead where I had arranged to get mail and fresh vegetables. (I soon learned that if I happened to come for my mail when there was a meal ready for the harvest hands, I would be welcome too.)

In those days, not much traffic passed Taylor Lodge. End-to-end hikers were rare; even some of the few hiking just from Bolton to Smugglers’ Notch might bypass the cabin, which was a tenth of a mile off the main trail. An occasional family might hike up, just for the day, from the Trout Club at Lake Mansfield. Weekends could bring a group of young people from nearby farms or a family from Burlington. Labor Day weekend was the only time the cabin reached its fourteen-lodger capacity. More often than not, I was the sole occupant of Taylor Lodge.

When I was there, Taylor Lodge was a long, low, dark brown (creosoted for preservation) cabin that saw neither sunrise nor sunset because of its location in the Notch. I do not remember it ever getting oppressively hot, despite its relatively low elevation, under 2,000 feet. My only view was from a small “back porch” a few yards behind the cabin, which afforded a vista down to Lake Mansfield. On one of his visits, my father painted that view, and he gave the painting to Mr. Riley, the manager of the Mount Mansfield Hotel. The picture hung in the hotel lobby for many years but I do not know whether it survived the demolition in 1958.

About the floor, space was occupied by bunks, with a good-sized table and benches on the right side. In the rear center was a box-type wood stove with a useful oven built right into the stovepipe, heated by the hot smoke passing around it. I only remember one hiker who carried a stove, a shiny brass kerosene-burning Primus. (I soon bought one for myself, which still works.) The water supply was a small stream a few hundred feet down the Lake Mansfield Trail, just far enough to make my hands hurt if I carried two full pails back up.

Caretaking chores were not onerous. I kept the cabin clean and supplied with firewood and water. I made repairs, replacing a broken window pane or applying a coat of creosote to the logs. I collected a fee of twenty-five cents from each overnight guest, which I turned over to the Burlington Section; my only salary was seventy-five dollars for the season. I cleared and maintained trails and signs. And sometimes I had to provide advice or assistance to people who knew less about being in the woods than I did. By the end of the summer, I felt very proficient with my saw and ax—enough so that I was able to win the sawing and chopping competitions at a Boy Scout event that fall, even beating farm kids who did chores year-round.

Early in the season, there was a prolonged rainy spell that discouraged hikers. In thirteen days not a single person even passed by the cabin. I hiked down to the farm to mail a letter to my mother, asking her to send me “the book that will take me the longest to read.” On my next trip out I picked up a package containing Shakespeare’s Complete Works. I read every play and sonnet in the book, and even memorized a few soliloquies and sonnets. I had never seen a Shakespeare play, so I was able to let my imagination put them on for me.

One evening during that period of solitude I heard voices outside my cabin. I had finished supper and it was already dark out. As I listened, it sounded as if three or four women were discussing something in front of the cabin, perhaps whether they should enter or not. Taking my lantern, I opened the door, intending to make them welcome. In the lantern light, I saw four porcupines ambling away from the fire ring. Lonely as I was, I did not invite them in.

Later that summer as I sat on the bench behind the cabin watching it get dark, I thought I heard a man’s voice calling. It seemed to come from the Long Trail south of the notch. I got my flashlight and headed that way. Sure enough, in about ten minutes I came upon a man sitting on a log. A guest at the Mount Mansfield Hotel, he had started that morning for a day hike to Taylor Lodge, carrying nothing but a box lunch. Somehow he missed the turnoff to the lodge, and walked quite a distance on the Long Trail toward Bolton Mountain. Realizing something was wrong he turned back, but was overtaken by darkness, so he stopped hiking and started calling. He was not looking forward to a night out in the woods.

I led him back to my cabin, where I cooked him supper and made up a bunk with my extra blankets. In the morning we had breakfast, and I offered to guide him back to his hotel. He said he could find his way in daylight, so I just walked with him to the trail junction and pointed him north. I wondered how the mountain hotel dealt with missing guests, but I learned later that he had never been missed. I also learned that he was a candy salesman. About a week later my mail contained a huge sample box of assorted Welch candy bars.

I did a lot of hiking, some in connection with my chores and some just for fun. There was the weekly walk to Stevensville for mail and vegetables. Sometimes I went by way of Butler Lodge to visit with the Lennetts, a couple from Long Island who were caretaking there. They had hiked the entire Long Trail the previous summer, and had been so taken by Butler Lodge that they applied to be caretakers. My walks to Mount Mansfield were usually just for fun. Once I visited Mr. Murray, a school teacher from New Jersey who was caretaker at Taft Lodge. Later in the summer I sometimes took a pail and joined farm families picking the lush blueberry bushes on the Forehead. I liked bushwhacking up the mountains nearer to Taylor, using my map and compass to see if I could go in a straight line to the summit.

When I couldn’t hike, and had no chores, I read. Besides Shakespeare, I read American history to get credits for the civics course required for graduation. My mother mailed me classics, including Mann’s The Magic Mountain and Buck’s The Good Earth. I kept an account book of my expenditures for food and postage, the lodge fees I collected, my income from the infrequent sale of meals, and an occasional tip. Canadian hikers were the most likely to leave a note of thanks with money pinned to it.

My season ended right after Labor Day, when I had to return to school. The cabin was full that holiday weekend with family groups, couples, and solo hikers. My sister Huddee and her girlfriend hiked in to spend a relaxing weekend with me. As we sat quietly on a bunk talking while waiting for the lunch crowd around the stove to thin out, there was a loud explosion, the oven blew apart, and Huddee started screaming. I ran for my shovel and water pail, for the fire in the stove was burning fiercely with no pipe to vent the smoke out of the cabin. I threw water on the fire, then started carrying glowing embers on the shovel to the fire ring outside. Huddee was still screaming.

Then I realized what had happened. One of the campers had put a can of beans in the stovepipe oven to heat, but she had not punctured the can first. The exploding can dislodged the stovepipe and sprayed boiling-hot beans onto Huddee. I flushed her with the other pail of water, and treated the small burns on her arm and leg. Then I aired the cabin, re-assembled the stove, carried the still-burning coals back in, and finally cleaned up the mess, which included baked beans stuck to the walls. More excitement in that fifteen minutes than I had had all summer. I know Huddee didn’t appreciate it, but there was nothing like finishing up one’s first caretaking season with a bang.

Loved this article. Wish I had known Daan. He must have been a fantastic person.

Caretaking is a great life and Daan lived it. With or without exploding beans!

It’s because of people like Daan that our end to end hike was possible, wish I could have thanked him for all his work.

Dan was a special friend of my father Bob Earley who died in May2019.HE went to UVM with Daan and hike with him and others.

Thank you for sharing this. Daan’s Memoir and his legacy are truly gifts. Hike on Daan.