Summer is a hot time of year for Vermont bugs. And while bugs are great — they pollinate vegetation; decompose dead plants and animals; and fuel the food chain — they can also threaten human health and wellbeing. Here’s what you need to know to protect yourself from some of the worst offenders around the trail.

Mosquitoes

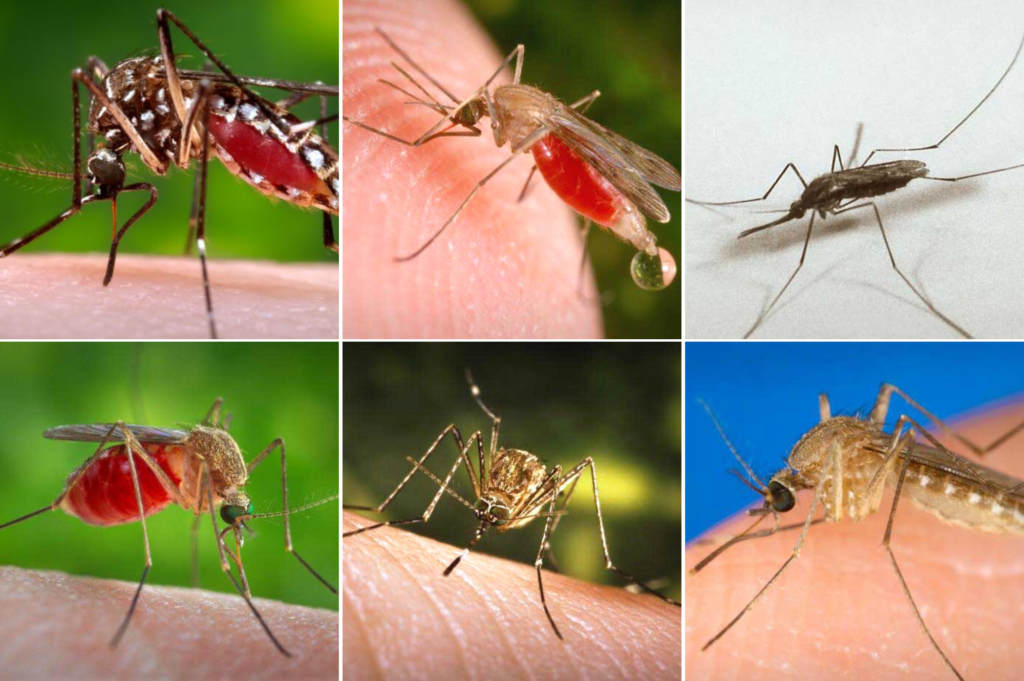

Over 200 types of mosquitoes live in the continental United States and its territories, according to the Center of Disease Control (CDC). Of these, 12 types of mosquitoes spread germs that can make people sick. In Vermont, mosquitoes have spread West Nile Virus (WNV) and Eastern Equine Encephalitis (EEE). It’s hard to tell which mosquitoes carry germs from nuisance mosquitoes, which bite without spreading germs. However, you can be sure every bite is from a female mosquito. Female mosquitoes need a blood meal to produce eggs.

When: In Vermont, mosquito season begins in the spring and poses a health risk by summer. By July, some mosquitoes may be carrying viruses that cause WNV and EEE, according to the Vermont Department of Health.

Where: All mosquitoes depend on water with little to no flow to lay eggs, although the type of water source varies between types of mosquitoes. (Learn more about mosquito habitats.) That means forested and wet trails — especially around swamps, ponds, and puddles — are a great breeding ground for these bugs.

Why: When a mosquito bites, it pierces your skin, sucks up blood, and deposits saliva in the process. The saliva commonly can cause humans to swell up and itch around the bite site. More severe reactions include a large, swollen, red area; soreness; low-grade fever; and hives.

How to protect yourself: To prevent bites and mosquito-borne diseases, wear long-sleeved shirts and pants; use an EPA-registered insect repellent, with active ingredients like DEET and oil of lemon eucalyptus; and treat clothes and gear with the insecticide, permethrin. Learn more.

How to treat mosquito bites: Wash the area with soap and water. Apply an ice pack to reduce swelling and itching. Apply an over-the-counter antihistamine cream to relieve itching or apply a baking soda paste. Learn more.

Black Flies

There are six black fly species in North America known to bite humans (more info). In Vermont, there are 40 species of black flies, of which only 4 or 5 species bite humans, according to the bug-loving folks who run the Adamant, VT Blackfly Festival.

In the United States, black flies do not cause disease. But like mosquitoes, female black flies require a blood meal to mature their eggs, and they prey on birds and mammals. These insects lay eggs in or on flowing water, and the young develop in large rivers, icy mountain streams, trickling creeks, and waterfalls — depending on the species.

When: These bugs are most active from mid-May to the end of June. Activity peaks tend to occur around 9:00 to 11:00 AM and again from 4:00 to 7:00 PM, according to the University of New Hampshire. Black flies tend to be most active on humid, cloudy days and just before storms; they do not bite at night.

Where: Black flies breed in flowing water, like streams and rivers and are common in humid, wooded regions during summer months.

Why: These biting insects will swarm humans and livestock, biting around the head, hair, and ears. Black fly bites are painful, as the bugs cut into the skin and lap up blood that pools into the wound. Bites appear as puncture wounds or a huge swelling. Common reactions include lymph node swelling and skin rash. View frequently asked questions.

How to protect yourself: Avoid infested areas, especially in the dawn and dusk during the summer months. Wear long-sleeve shirts and long pants, a head net, and light-colored clothing, as black flies are attracted to dark colors. More info.

How to treat black fly bites: For mild bites, wash the area with soap and water. Use a cold compress to reduce the swelling and irritation, and use an OTC antihistamine or anti-itch cream to treat itchiness. More info.

Blacklegged Ticks

Six of Vermont’s 15 tick species bite humans and can transmit diseases. The blacklegged tick, however, causes 99% of tickborne diseases (including Lyme Disease) reported to the state, according to the Vermont Department of Health.

When: In Vermont, peak activity for the blacklegged tick typically occurs in May and June when nymphal ticks are looking for a host; a second uptick occurs in October and November when adult female ticks are looking for another host before winter. However, these arachnids are active any time of year when temperatures are above freezing.

Where: Blacklegged ticks are found throughout Vermont, living in wooded areas and fields with tall grass and brush. These bugs are generally found near the ground; they can’t jump or fly, according to the CDC.

Why: After hatching from an egg, ticks must eat blood at each developmental stage — six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult — to survive. Most ticks prefer to have a different host animal at each life stage.

If a tick attaches to a host animal with a bloodborne infection, the tick will ingest these pathogens with the blood. Ticks also pass on saliva to the host animal while feeding, and can pass on a pathogen. In this process, these bloodsuckers become vectors, passing pathogens from one host (such as a mouse, chipmunk, or white-tailed deer) to the next (e.g. humans) throughout development. View diagram.

How to protect yourself: Avoid areas where ticks live; use EPA-registered tick repellents; and cover up with long-sleeve shirts and long pants. Check clothing, gear, and pets for ticks before going inside; and check your body for ticks, especially under the arms, behind ears, around the waist, and between the legs. More info.

How to treat tick bites: Remove ticks as soon as you can with fine-tipped tweezers (more info). Do not use petroleum jelly, a hot match, or nail polish to remove ticks.

Watch for symptoms — including fever, chills, rash, headache, joint pain, muscle aches, and fatigue — and tell your health care provider if you get sick. Some tick-borne illnesses, like Lyme and anaplasmosis, can be treated with antibiotics.

What bugs get under your skin, either literally or metaphorically? Let us know in the comments which Vermont bugs you want to know more about!

Leave a Reply