This article was written by Vic Henningsen and previously appeared in the Spring 2020 Long Trail News. Historian and former VPR commentator Vic Henningsen was a caretaker and ranger-naturalist on Mount Mansfield during the 1970s.

There’s an old story about a pair of caretakers at Butler Lodge in the 1930s offering porcupine stew and blueberry pie for sale to hungry hikers. The catch: you had to buy the stew to get some pie.

It’s partly true. That was the Great Depression. George and Martha Wallace sold candy bars, Kool-Aid, homemade cookies, and – yes – pies baked in the stovepipe to augment income from the 25-cent overnight fee. As for porcupines, George reported:

“We found porcupines quite edible . . . the younger ones were fairly good. Their livers were a special delicacy; often we were wasteful of resources and ate only the livers. By the end of the summer, we almost, but not quite, ran out of porcupines.”

Ignoring famished hikers, the Wallaces hoarded porcupines for themselves. A disastrous experiment with red squirrel stew confirmed the wisdom of their choice.

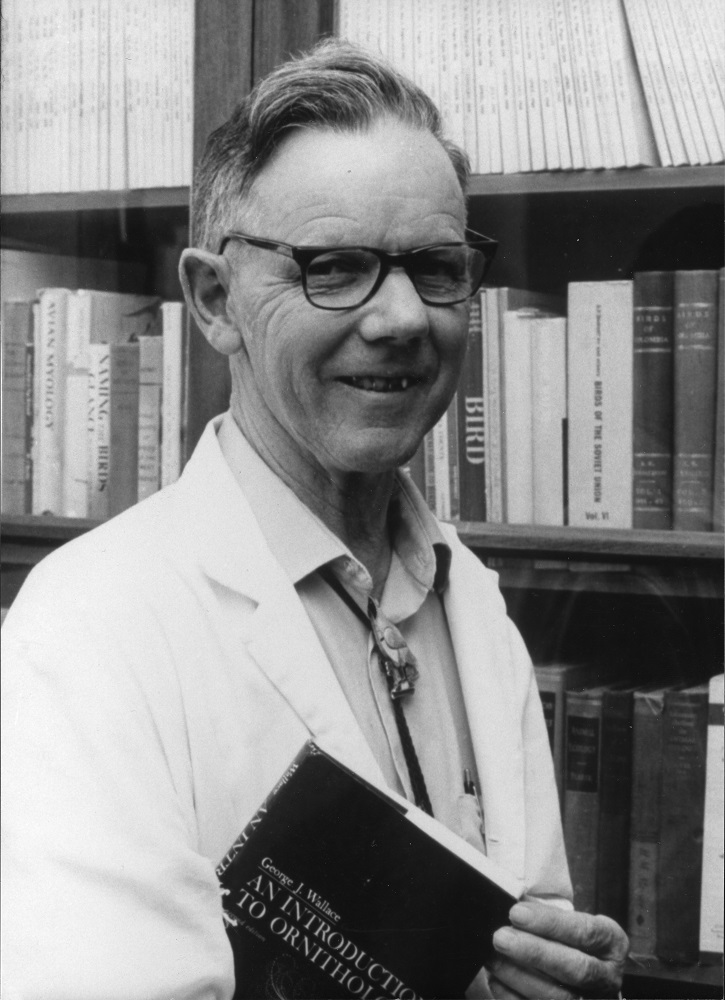

A lifelong ornithologist, George J. Wallace (1907 – 1986) of Waterbury was pursuing a Ph.D. in zoology. His dissertation examined the Bicknell’s thrush, native to the higher slopes of Mount Mansfield, where he conducted research while caretaking at Taft Lodge in 1933 and, after his marriage, with Martha at Butler Lodge in 1935 and 1936.

Bicknell’s thrush, Wallace noted, was “one of the shyest, rarest, and least known” of American birds. “Its choice of the bleakest, most isolated, and inaccessible habitats, and nesting as they did in the most impenetrable tangles, made it difficult to study.”

Wallace, however, was patient and persistent, learning to locate nests and track the birds. Once he even rescued a sickly young thrush, which he and Martha nursed back to health. Bathing in a special dish, “Bicky” was a brief Butler star until he mistakenly dove into a pot of scalding water and died. The Wallaces later rescued another thrush, inspiring National Geographic magazine to capture the scene before Bicky II was released into the wild.

Meanwhile, the Wallaces followed a familiar routine: sweeping the lodge every morning, replenishing the woodpile, maintaining local trails (and, in their case, building what became the Wallace Cut-Off), educating visitors about mountain flora and fauna, greeting hikers, and wondering how full the lodge would be that evening (their record was 32!).

They moved in through deep snow on Memorial Day weekend, packed their supplies down over the Forehead cliffs from the old Mount Mansfield Hotel, and left after Labor Day as autumn rains began. One of the few caretakers to work at both Taft and Butler, Wallace’s preference for the latter was clear. Referring to Taft as “a rustic, somewhat rundown log cabin” he waxed eloquent about Butler, built during his first season on the mountain, and gloried in the view from its doorway:

“Often at sunset the waters of Lake Champlain shone like a sea of gold. In the mornings great banks of snow-white fog hovered over the valleys below, then rose and dispersed slowly, bathing the mountaintop with mists for hours or even all day.”

Wallace was the first caretaker to use the position as an opportunity to further his research – “to unite” as Robert Frost put it,

“my avocation and my vocation

as my two eyes make one in sight.”

He would not be the last.

Honed on Mansfield, his talent for meticulous scientific observation led Wallace to a career as a professor at Michigan State University, where he later became a central figure in one of the major environmental controversies of the 20th century.

During the mid-to-late 1950s, Wallace and his students documented widespread robin die-off on the MSU campus which, their evidence suggested, derived from spraying the pesticide DDT to combat Dutch elm disease. DDT killed the beetles carrying the disease, but lingered on leaves and soil to be consumed by earthworms, which in turn were eaten by campus birds. After recording more than 100 bird species showing signs of DDT poisoning, Wallace took the risk of publishing his preliminary data, arguing that waiting years for more complete documentation “will be too late.”

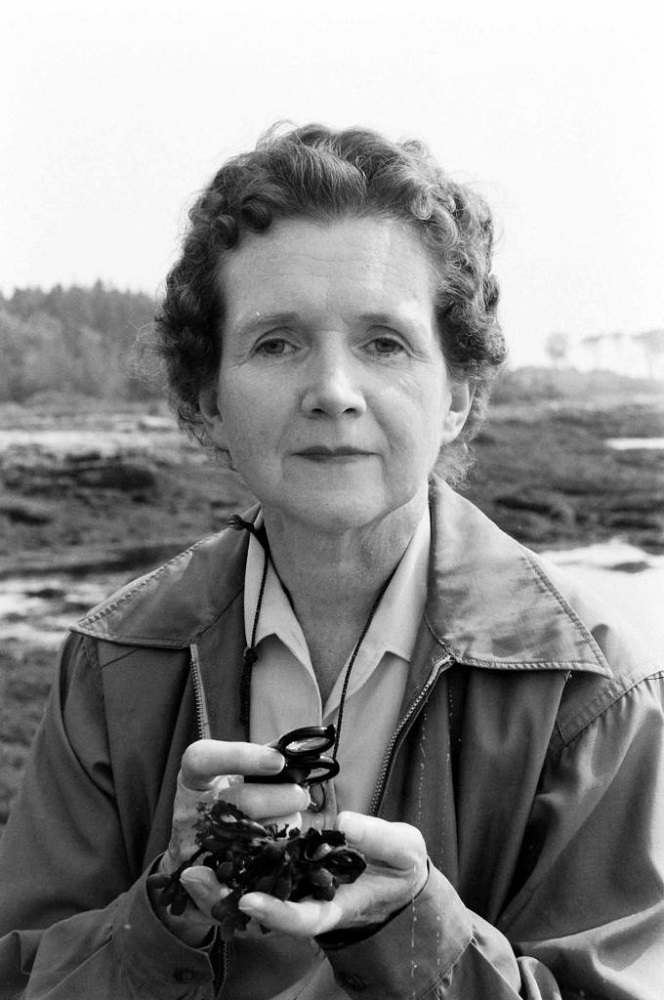

Wallace’s report caught the eye of Rachel Carson, a marine biologist and brilliant author whose gift for explaining complex science in clear, lyrical prose made her the best-known science writer in America. Her work paved the way for writers like Terry Tempest Williams and Bill McKibben. Carson was researching government policies that permitted industries to introduce toxic substances into the environment without considering long term consequences. She was electrified by Wallace’s findings, and their subsequent correspondence significantly influenced her thinking about the ripple effects of pesticide use and influenced her book Silent Spring.

It is difficult to overstate the impact of Silent Spring. Carson’s blunt moral challenge to heedless government and industrial ecological destruction revolutionized public opinion, and helped spark the modern environmental movement. Carson’s work influenced passage of the Clean Air Act, the Wilderness Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act, and led to a ban on DDT and to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Historians regard Silent Spring as one of the most influential books of the 20th century.

The conclusions of Carson and Wallace were brutally attacked. Carson died in 1964, two years after Silent Spring appeared, but Wallace endured years of efforts to discredit his work. Michigan State was heavily funded by chemical and agricultural corporations deeply invested in production, marketing, and widespread use of DDT. They orchestrated a smear campaign, challenging Wallace’s methods and his conclusions. His funding dried up, his graduate students left, colleagues shunned him, the university tried to fire him. He was saved only by the timely intervention of Michigan Congressman John Dingell Jr. Impressed by Wallace’s testimony before his Congressional committee, Dingell threatened to block all federal funding for MSU if he was terminated.

Wallace continued to research and teach, paying little attention to the conflict swirling around him. His autobiography devotes only four paragraphs to the DDT controversy, but ten pages to Mount Mansfield. Although further research has long confirmed his early findings, he has been largely overlooked, unlike Rachel Carson. But without his contributions, Silent Spring might not have become one of the most influential books of the century.

George Wallace’s legacy continues on Mount Mansfield in the research of scientists at the Vermont Center for Ecostudies, whose studies of the Bicknell’s thrush, blackpoll warbler, and other mountain birds command international attention. But recent reports of worldwide avian species declines of 25 to 30 percent since 1970 reinforce the urgency of Wallace’s inspiration and encouragement of Rachel Carson. Environmental activism, he wrote, “needs doing now. Twenty years from now . . . will be thirty years too late.”

Wonderful article and very timely. Hopefully mankind will have a collective epiphany and stop our suicidal abuse of our only habitat, Earth.

Thank you for your wonderful article. George Wallace is the great uncle of my husband and I’ve heard the stories about him being smeared for his unyielding devotion to DDT research and how after his death, MSU actually reversed course, recognizing Dr. Wallace with an honorary Ph.D. Today, MSU honors Wallace with the George J. Wallace and Martha C. Wallace Endowed Scholarship for graduate students working with birds.

Also of interest during these CV-19 days is that George’s father, James Wallace died in 1918 of the Spanish Influenza when George was 11. The October 9, 1918 Waterbury (VT) Record’s first obituary was “JAMES WALLACE, Prominent Blush Hill Farmer, a Victim of the Prevailing Distemper….survived by his wife, Florence Richardson Wallace and seven children”. All seven children suffered from and thankfully survived the flu. Their mother, Florence, remarkably did not get the flu, claiming she was too busy caring for everyone else to get sick.

George wrote in his family history “there were suggestions of breaking up the family and putting the children in foster homes, but mother said ‘no’ quite emphatically”. She had a lot of support from the Methodist church, family, and neighbors, who helped with the farm chores. Florence was very hopeful that all her children would have a college education, since she and James never had the chance to pursue higher education. The boys all staggered their high school and college years so that at least one was always home to work the farm. All seven children graduated from college, with George receiving an A.B., M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Michigan.

Thanks to K. Alan “Wally” Wallace, nephew of George for his meticulous genealogy research and providing most of the information for this comment. Wally resides at the Blush Hill Farm with his sister, Rosina, persevering after the devastating 2018 farm fire.

If you want more information on Dr. Wallace’s impact on stopping DDT, check out the 2007 George J. Wallace: Dying to be Heard Documentary https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNJ3diDXl-4

Thank you so much for sharing this!

Wow! What an impressive family and story. Can one bike to Butler Lodge to view the Bicknell Thrush?

No, there is no biking permitted on the Long Trail or side trails.