This post was written by Anna Gardner in August 2022. Crew continued work on Burrows every week until October 14, 2022, for a total of 128+ work sites.

Tens of thousands of hikers (and dogs) climb the Burrows Trail on Camel’s Hump each year, and it shows. “I could see the trail widening and where people were stepping,” said Kathryn Wrigley as she pointed out a section of the trail about four feet wider than it was a few years ago. Popular hiking trails saw an enormous increase in use during the surge of outdoor recreation during the pandemic, and the Burrows Trail was hit harder than most.

Kathryn, a forest recreation specialist for the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation (FPR), and Keegan Tierney, Green Mountain Club Director of Field Programs, considered the flow both of hikers and water as they studied every inch of the 2.1-mile trail to plan a three-year, $750,000, top-to-bottom rehabilitation.

In June the GMC’s Long Trail Patrol broke ground on the largest trail rehabilitation project in the club’s modern history. A typical trail improvement takes two to six weeks and fixes small stretches of trail. Crews from five organizations will spend 116 weeks in three seasons on the Burrows Trail to mitigate the effects of erosion, climate change, and increasing foot traffic.

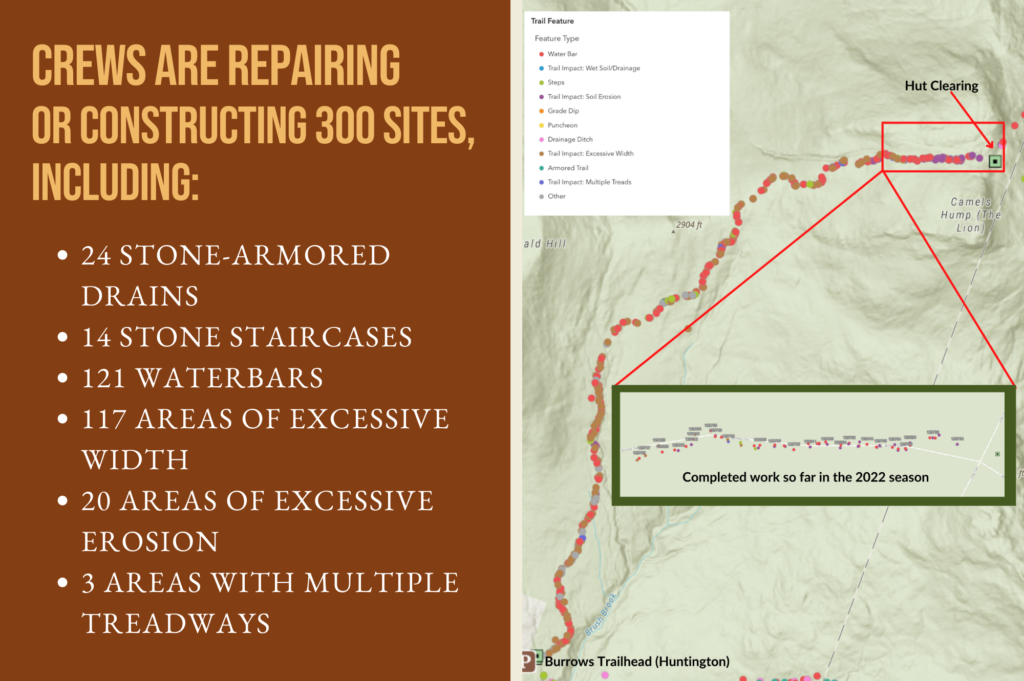

Justin Towers joined GMC in February as the full-time coordinator managing the Burrows Trail crews and more than 300 work sites. With a $250,000 allocation from the Vermont Legislature and a $210,000 Enhancement of Recreation and Stewardship Access (ERSA) Trail Grant, GMC and FPR hope to tackle the whole trail at once, though about $290,000 more will be needed. The all-in approach is almost unprecedented in Vermont, but should work well for this and other popular steep trails in bad condition.

Formerly known as the Huntington Trail, the century-old Burrows Trail goes straight up the fall line of the mountain, which is also the easiest route for water to flow down (view a video explanation here). Heavier and more frequent rain from climate change has worsened the cobble-lined streambed the trail has become. The project will also address excessive widening, up to 20 feet in places, caused by increasing traffic and hikers trying to avoid mud or pass others.

Planning the Burrows Trail Rehabilitation

Kathryn and Keegan started planning in 2018, initially for a two-week project focused on waterbars scheduled for 2019. Instead, Kathryn proposed rehabilitation of the whole trail, and the idea was a hit. They first considered re-routing sections of the trail below 2,500 feet. However, wet soils, a series of drainages, and scientific study plots that couldn’t be disturbed, all precluded major relocation, so they decided rehabilitation on the current route was most efficient. They also planned to keep the trail open to hikers throughout the rehab.

Since they hadn’t planned such a large project before, Kathryn and Keegan studied a similar trail project on the Crawford Path in the White Mountains, also a historic Eastern fall-line trail. They learned they would need a lot of money and multiple trail crews working together to accomplish such a big job quickly. They drafted a budget based on the Crawford Path budget that accounted for the cost of materials, the varying skill levels of crews, and more.

In 2021 Kathryn spent eight days on the Burrows Trail, painstakingly identifying more than 300 sites for work. She adopted a hiker’s mindset to envision why they often stepped off trail, widening the main treadway and creating social trails, and she looked both uphill and down to conceive a good design. “It can sometimes be difficult to pinpoint what is causing a particular trail ‘problem,’ until you turn around and see a large rock or poky branch that is deterring the downhill hiker from staying on the trail.” Using the ArcGIS Collector app she recorded waypoints at each site, with photos to document conditions, adding notes specifying repairs and construction: waterbars, check steps, staircases, and widening.

Kathryn also noted required skills to help allocate crew time and assignments. Youth and volunteer crews can brush in social trails and repair waterbars, but professional crews like GMCs Long Trail Patrol are needed for skilled and strenuous rock work.

Partnerships and Funding

The size of the Burrows project means that GMC and FPR will call on volunteers and long-standing partners: in addition to the Long Trail Patrol, the Vermont state trail crew; the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps; the Northwoods Stewardship Center Conservation Corps; and the National Community Conservation Corps. Partnerships yield new ideas, opportunities and approaches. “We have a robust system of trails for various user groups and a strong network of non-profits and contractors who support the development and maintenance of those trail networks,” Kathryn said.

The $460,000 already secured for the project is an amount that’s unheard of for such a small linear footage of trail, according to Keegan. GMC continues to apply for grants and was recently awarded a $30,000 grant from Athletic Brewing’s “Two for the Trails” Fund. The club is also actively seeking private funding to complete the project. If you support sustainable management and maintenance of our trails, you can make a gift today.

Work Progress on Burrows Trail

The ambitious top-to-bottom approach to the project is necessary to promptly counteract the effects of climate change, storms, and heavy use.

The goal of all trail improvements is twofold: steer water off the trail; and steer hikers onto a durable treadway. So Justin’s crews consider both the path of water and the behavior of hikers. “I follow what the water is doing, and assign tasks to slow it down, which reduces erosion,” said Justin. Addressing hiker behavior, Kathryn visualizes what the hiker sees when upward and downward bound, and determines how to make the durable path appealing.

Stone is the most common durable material in Vermont, so most rehab work is rock work, requiring lots of highly skilled manual labor. Crews find, dig out, move, and set rocks one by one, using strength, strategy and time. Though it may take a full day to set one rock, setting rocks precisely ensures they will stay put for decades.

Burrows crews frequently employ highlining. For this technique, a strong cable (highline) is strung between trees; then, a heavy stone is braked or pulled slowly below the highline using tension applied by a Griphoist (see video demonstration here). Highlining is easier, quicker, and safer than wrestling rocks on the ground, and it avoids damaging land by dragging rocks along a mossy forest floor.

This summer Justin’s crews started at the top of the Burrows Trail near the Hut Clearing, working their way downhill for maximum effectiveness. Diverting water from the trail at its top reduces flows all the way down. Of course, at higher elevations crews must take special precautions. The top of Burrows is in the subalpine zone, so fragile vegetation must be protected when quarrying and moving rocks.

Crews camp at their backcountry “spike” site five days a week, and work in sun, rain, heat and bugs. The job is challenging, but also rewarding. GMC Long Trail Patrol member Emily Hollander recalls her first time highlining rocks as memorable. And, says coworker Max Millslagle, “It’s a legacy project, which is neat. It’s cool to think that this stuff is going to be here 50 years from now.”

What’s Next for the Burrows Trail Rehabilitation?

Trail crews will continue working their way down the Burrows Trail over the next three seasons. The three-quarters of a mile closest to the top of the trail, approximately 100 work sites, should be complete by the end of the 2022 field season, but there are many variables, including weather, staffing, and funding, that can affect progress.

Since the Burrows Trail Project is an intense, expensive, large-scale project happening in a short timeline, it is setting a precedent for future trail maintenance and management. Many other historic fall-line trails in the Northeast present serious deferred maintenance challenges, but have no money to meet them. Most can’t be replaced by new routes. “Rebuilding these routes in place and improving their sustainability using the techniques we are using on Burrows allows us to preserve these historic trails without affecting their character or difficulty,” said Justin.

One third to one half of the Long Trail needs major repairs or upgrades to withstand higher traffic and increased storm intensity, according to Keegan. The same strategies used on Burrows Trail will likely be used on the Long Trail as well.

Restoration of the Burrows Trail will prove once again the value of long-term cooperation like the partnership of FPR and GMC, which has leveraged funds, expanded the number and types of trail crews working on the Long Trail System, and made long strides in a new direction for trail rehabilitation. Keegan hopes the project will also inspire more people to get involved – to work, volunteer, donate, and advocate for maintaining our backcountry assets and resources.

Trail improvements and awareness create more opportunities and new ways get people out on the trails, embodying the Green Mountain Club’s century-old mission statement “to make the Vermont mountains play a larger part in the life of the people.” Free trails welcoming all hikers are an extraordinary resource. We ask hikers only to “Please stick to trails, walk through mud [rather than around it], and remember that many people enjoy this place – so leave it better than you found it,” as Kathryn says.

Follow the Burrows Trail Project & Support our Work

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2022 edition of the Long Trail News under the title “Rehabilitation of Historic Burrows Trail Commences.” It was written by Anna Gardner, who served as a Burrows Trail Project Content Creation Intern, working with both GMC and FPR during the 2022 summer.

Anna was out in the field with the Burrows trail crews two to three days a week, capturing photos and videos and sharing weekly updates on GMC’s social media and website, helping the club document this historic project. Anna is heading into her senior year at UVM’s Rubenstein School, where she is studying for a degree in Parks, Recreation, and Tourism. In her spare time Anna enjoys freeskiing and spending time at her family camp in the Adirondacks.

Leave a Reply